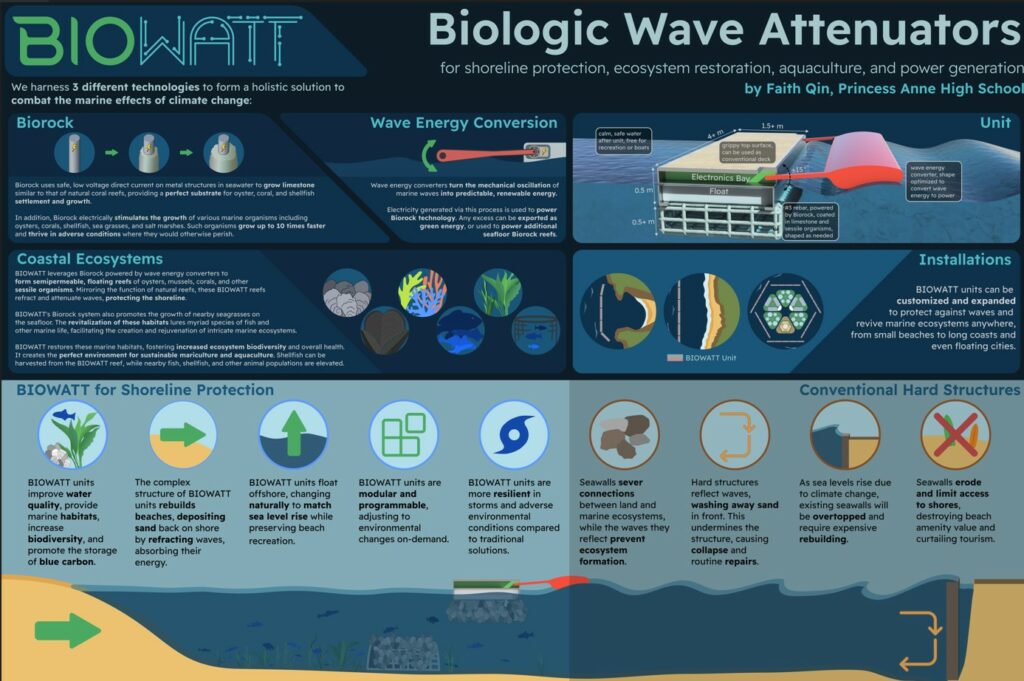

I met 16-year-old Faith Qin at the Innovations in Climate Resilience conference hosted by Battelle Memorial Institute. Among hundreds of scientists, researchers, and representative from organizations and companies focused on climate change resilience, Faith presented her work on oyster restoration and shoreline rehabilitation. Faith was Battelle’s Youth Climate Challenge award winner, besting hundreds of entries from across the country. The competition asks young people from 9th – 12th grade to research past and future impacts of climate related hazards in their community and develop a proposed action to help build a more resilient community. For more information on Battelle’s Climate Challenge competition, you can follow this link: https://www.futureengineers.org/battelleclimatechallenge

If you’d like to learn more about Faith’s work, you can connect with her through LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/faith-qin/

Faith and I had a great conversation at the conference and she agreed to be interviewed for this blog. This interview took place on May 17th, 2024, over Zoom.

Naomi: Faith, thank you for being here. Let’s get started with the basics. You recently won Battelle Memorial Institute’s Youth Climate Challenge Competition. Can you start with describing the problem you wanted to tackle?

Faith: Yes, the two main issues I want to tackle, which is related to my own location in Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, is the loss of oysters and shoreline erosion. Oysters have great abilities to filter water, clean out microplastics, nitrates, and phosphates to prevent eutrophication. There’s been this oyster restoration effort that’s happening for years, but none of it has actually helped to spur oyster growth fast enough. Oysters require calcium carbonate to build their shells, and so do corals, which are extremely threatened. But people don’t really hear about oysters because they’re ugly, right? Unlike corals, no one’s really going to dive for and preserve oysters. The economic benefit for oyster restoration and the nature services it provides is harder to categorize than with corals. You can talk about how the loss of coral reefs hurts tourism, but not oysters. But both are important. Shoreline erosion is a growing concern alongside rising sea levels. Current approaches such as seawalls and beach nourishment are unsustainable, costly, and can even damage marine ecosystems. Close to where I live is Tangier Island, a small fishing island which will soon be underwater in the next 50 years. There is a dire need for more innovative and sustainable solutions against shoreline erosion.

Naomi: What oyster restoration efforts are currently happening?

Faith: Our current conservation efforts do not meet the standard. Some of the most common efforts involve just putting in concrete igloo structures, call reef balls, for the oysters. The reef ball does not provide additional aid to growing oysters and has limited effectiveness. Another popular restoration effort is planting spat, baby oysters, on dead oyster shells and dumping that in the bay. This also only has limited effectiveness as no nutritional or growth aid is given. You’re not giving them any extra calcium carbonate to build their shells. But with Biorock technology, which has been around for about 25 years, oysters and other attached sessile organisms become more resilient to changing temperatures and ocean acidification. Oysters and corals are able to build their shells at rates of up to 10x as fast and survive harsher climates. It’s difficult to sit by idly when you know there are better solutions for oyster restoration than are currently being implemented.

Naomi: So tell me about your project to help the oysters.

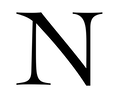

Faith: My proposal combines three different technologies. It consists of a Biorock reef connected under a floating dock base structure, which is then attached to a wave attenuator/wave energy generator. For biorock, which is the most important portion, I used rebar mesh to create a reef structure. I then ran a very low voltage of electricity through it, from seven to nine volts. Through electrolysis, a cathode, which is rebar mesh in this case, and a sacrificial anode, I use platinized titanium, calcium carbonate is precipitated out of the water and grows on top of the rebar mesh. This serves as a great environment for sessile organisms such as oysters and corals. So, if you’re in the tropics, you can put coral reefs on Biorock and it will help them withstand the rising ocean acidity and temperature to make them more resilient. What we expect and have found is that when used with oysters, they can also grow with rates up to ten times faster.

Naomi: And this same process would help with coral reefs?

Faith: Right, so biodiversity is what strengthens ecosystems against change, whether that be from an invasive species or rising sea level temperatures and changing ocean chemistry. If we want our ecosystems to survive, we cannot take out corals. Corals are such a vital keystone species. Within their ecosystem, they provide shelter promoting growth, activity, and biodiversity. These same attributes apply to oysters. They provide a great habitat for fish to roam and seagrasses to grow, not to mention simultaneously cleaning the water. These ecosystem benefits, they multiply, so for example the growth of seagrasses will hold on to the sand and mud to prevent erosion from happening.

Naomi: Tell me about the wave attenuator. How does that work?

Faith: The wave attenuator and energy convertor is mostly conceptual at the moment. I would love to hash it out more, but I need resources – like a team of scientists who could help. But the idea is we would attach a converter to the floating dock base structure. The converter serves to catch the wave, generating energy, and then attenuate it, eliminating or at least reducing the wave so it does not erode the shoreline. The Biorock reef structure also helps to break the wave energy, allowing waves to come in more gently, protecting the shoreline and depositing sand back.

Naomi: So you’ve tested the biorock piece, but not the wave attenuator?

Faith: Right, so I’ve tested the actual Biorock portion for Chesapeake Bay deployment with oysters in the Lynnhaven River and it worked. I would like to get the attenuator built and tested for how much energy it could actually produce, and answer questions like can it produce enough energy? How many sister reefs could it power? Is it economical to possibly scale it up and feed energy back into the electricity grid as a form of renewable energy?

Naomi: What do you need to make that happen?

Faith: First, I would need the human resources to help me design and build the actual wave attenuator. Engineers from all different fields, like electrical and mechanical, would be greatly appreciated! I would need to factor in the costs of human resources, plus the materials to build. I received that $5000 grant from Battelle, which helps as a jumping off point. I’m hoping for additional support from other organizations that can provide me with a place to test the prototype and scientists so I can work on it this summer!

Naomi: Let’s switch gears here for a bit. You mentioned this biorock technology has been around for years, but people aren’t using it. Do you think with climate change issues, is the problem more about people not seeing the urgency, just not understanding it? Or do you think it’s that people are just motivated differently and aren’t prioritizing those issues?

Faith: I think people know the issues, but the urgency hasn’t been stressed enough. But once you start stressing the urgency, people are like, whoa there! Slow down. We don’t want to cause panic. We don’t want people to lose hope and be like, Oh my God, we’re going to die! That’s not the point. So we’re told to slow down the rhetoric, but then people aren’t getting how urgent it is. I think there are a lot of people who understand there’s a problem, but only a sliver of them understand how urgent it is. We need to do something, we need to do it now, and we need to stop looking at only the economic side of things. It seems like the people who are making decisions in politics are only looking at the economic side of things. And they’re just more concerned with their own well-being and living today, and not if the Earth will actually still be here tomorrow.

“We need to do something, we need to do it now, and we need to stop looking at only the economic side of things.”

Naomi: I know you can’t speak for your whole generation, but in your opinion, do you feel like the young people you know and talk with you have a good sense of the urgency of this situation? And do you feel like there’s a generational difference in how people grasp this urgency?

Faith: I definitely feel there is a generational difference in approach and understanding. I’ve heard more climate change talk among my peers and I than I have with adults. But there’s also what you concern yourself with, because my generation, we don’t have to worry about things like income, housing, and taxes. Maybe we have more time to think and read and educate ourselves about these issues. I’ve also seen the term Boomerang generation thrown around for younger adults who end up living at home because it’s so hard to support themselves. Sometimes people are just concerned with many other present things, and that’s understandable. Like if you can’t even support yourself, how are you going to advocate for an issue as broad as climate change? But I also think we’re getting better at educating the younger generation and bringing climate into the curriculum. There’s also an issue with getting overwhelmed with all the climate change talk. I think after a while you can just become numb to it, or you don’t talk about it as often as you should. And there’s also the feeling of, well, what can we do? Like, what’s the point of talking about if we can’t do anything?

Naomi: I recently heard about therapists who specifically treat climate change related depression and anxiety.

Faith: Right, I’ve heard of that too. I feel that if young people rallied Congress and the politicians to do something, and they actually did what was asked, we probably wouldn’t be feeling this way. Generally, in life, what I’ve found is that burnout occurs when you put in tremendous effort and see no results. And I think with many of these issues, you put such a tremendous effort in, as seen with major protests, and there’s maybe a tiny little concession. I think of Greta Thunberg with all of her climate activism. You put such an extraordinary amount of effort in. There are all these school walkouts, but then nothing actually happens because of economics and politics. Governments say, oh, we can’t do XYZ, whether that be cutting down fossil fuels or building green infrastructure, it costs too much, it will hurt the economy. They can’t quantify positive changes towards a green economy and what they’re saving for the future, so it doesn’t count. We need to stay focused on the urgency of the situation and try not to get burnt out.

Naomi: Let me ask about something a little different. Do you feel that scientific fields like this are pretty equally populated by women and men now, or do you ever feel like you’re in the minority as a woman in this field?

Faith: (Laughs) I 100% feel like I’m in the minority in this field. I run a STEM club for my school called the Princess Anne High School Maker Club and it is predominantly male. Out of around 30 members, only five of them are girls. So it’s like a one to six female to male ratio.

Naomi: Why do you think that is? It feels like there’s been a lot of movement to encourage young girls to go into STEM fields.

Faith: I would say, despite all of the encouragement, it seems if you go into the STEM field as a woman, there’s a certain stereotype about you that deters some woman. Like women in the STEM field are very aggressive or reluctant to change, or just very stubborn or unfeminine. But for men, there’s no negative stereotype like that. It’s just seen as normal.

Naomi: Okay, so let’s talk about something often considered “normal”. Your senior year in high school is coming up. What’s something that you’re really excited about, science or not science? Just something you’re looking forward to.

Faith: So the first thing that jumps out at me is college apps in the fall. I’m ready to put myself out there and be like, hey, this is me. I want to continue my education with climate science, biochemistry and engineering in college. So that’s the Fall, but in general, I’m excited at the prospect of being taken more seriously because I’m older. I mean, being female, plus being young, I think my proposals will get more traction when I’m older. Being older will open up doors on who I can work with, what companies or organizations, plus the grants that I can apply for. So I’m really excited about the future!

Naomi: This has been such a great conversation. One last question. If you could tell the leaders in charge of our nations one thing about climate change, what would it be?

Faith: Right. This was a pretty hard question for me to actually reckon with because there’s so much anger against governments and their inaction. I would tell them that climate change, it’s here, it’s now, it’s real. Who cares about the economy and whatever nations we’re fighting right now? In the big picture, none of that is going to matter. People don’t even realize how many ecosystems benefits these keystone species, corals, and oysters bring to you. You don’t realize it until you’ve lost it. In the past, we’ve covered wetlands with concrete just to build properties, and you don’t realize the biodiversity and benefits that wetlands bring to the surrounding area until you’ve lost it. Currently, we can’t economically quantify that. You can’t be only focused on boosting the economy and not take a stand to look at protecting the future, protecting not only humans but the other organisms that also inhabit this earth with us. We are in the sixth mass extinction, and we are the main driver of it. Freshwater species are the most harmed with three fourths already extinct since 1970. We have also lost about half of all biodiversity. Scariest thing is, you don’t realize what you’ve lost until it’s never coming back. A lot of medicines that we produce, they’re found from trees and they’re found from compounds in nature that we synthesize. You don’t know how many treatments we’ll lose by destroying all these ecosystems. So I would really tell them that focusing on only economics is a very dangerous path and is selfish. We cannot let our actions benefit just one person or just one nation, and disregard everyone else. We can see this selfishness through the climate inequality that’s been happening where the nations that contribute the least per-capita carbon emissions stand to experience the worst of the consequences. Some of the poorest nations in Africa and places like India will bear the brunt of global warming. Plus, climate migration in the future is going to be a huge issue. You don’t realize the hole that you’re digging yourself into when you talk only about economics. Even if you want to go the economic route, look at the cataclysmic economic costs that are going to be in the future if climate change isn’t stopped.

“We can turn fear and anger into action and motivation to change the future.”

Naomi: Any advice for the everyday citizen?

Faith: I know it can be very easy to block out these messages that you’re hearing because it’s hard to hear, and I know it can seem like you yourself can’t bring any impact. At times it feels as if you’re just suffering by yourself in your own mind. I would encourage everyone to look outside of your own home and within your community for other likeminded folks, or to look for organizations that you can join. You can volunteer, raise political concern, and create an outlet to voice your concerns with a community that’s there with you. I think what I’m trying to get at is, don’t block out all the terrible things that you’re hearing will happen because of climate change. Understand that it’s real. You can’t change the fact that it is happening. However, each individual person can something about it. If there isn’t an organization where you are, start one. Bring together people from your neighborhood. Go to coffee shops and bring people together who are also concerned with this issue. We can turn fear and anger into action and motivation to change the future.